From fighting developers to protecting nesting habitats, it’s a busy season for the Turtle Patrol

Posted Jun 30, 2021 04:44:00 PM.

It is turtle nesting season — the time each summer when a female turtles lay a couple dozen eggs, most (or all) of which will not survive in the end — which means Paul Turbitt, an amateur wildlife photographer and one part of the larger (and informal) Turtle Patrol group, is out along an abandoned rail line near Middle Sackville, looking for nests, just as he is most days around this time of year.

“You’re my third different walking partner this week,” he says, walking down the rail line, nosy reporter in tow.

Turbitt can pick out toads, snakes, beavers, you name it. But it is the plight of Nova Scotia’s turtles that holds Turbitt’s fascination most.

Each year, it seems to him, there are reports of turtles being run over by vehicles, or having their habitats destroyed — sometimes by poachers, or sometimes indirectly by the raccoons that come along with new subdivisions.

To him, turtles are an overlooked, if not completely forgotten, part of the ecosystems that our planners are tasked with managing.

“I was an I.T. guy that became an amateur wildlife photographer, and discovered the threat to snapping turtles because they were in my backyard,” Turbitt says.

In 2016, he started an informal Turtle Patrol group to help protect turtles and to advocate for their conservation. Each year, they were able to find more and more turtle nesting areas.

“2018 comes along, and we have an even better year,” Turbitt says. “We talked to the city, and the city was prepared to give us some seed money. In 2019, we became an association.” That year, they were able to find even more turtles, he said.

While the precise makeup of the Turtle Patrol may change — perhaps naturally, for any loosely organized coalition like this — their desire to push forward the issue of turtle conservation (and indeed, wildlife conservation more generally) hasn’t.

“We see our role to be education,” he tells me. “They’re water cleaners. Turtles are good. They eat decaying matter which raises the oxygen level in your lake, so they’re good for the fish, they’re good for the water.”

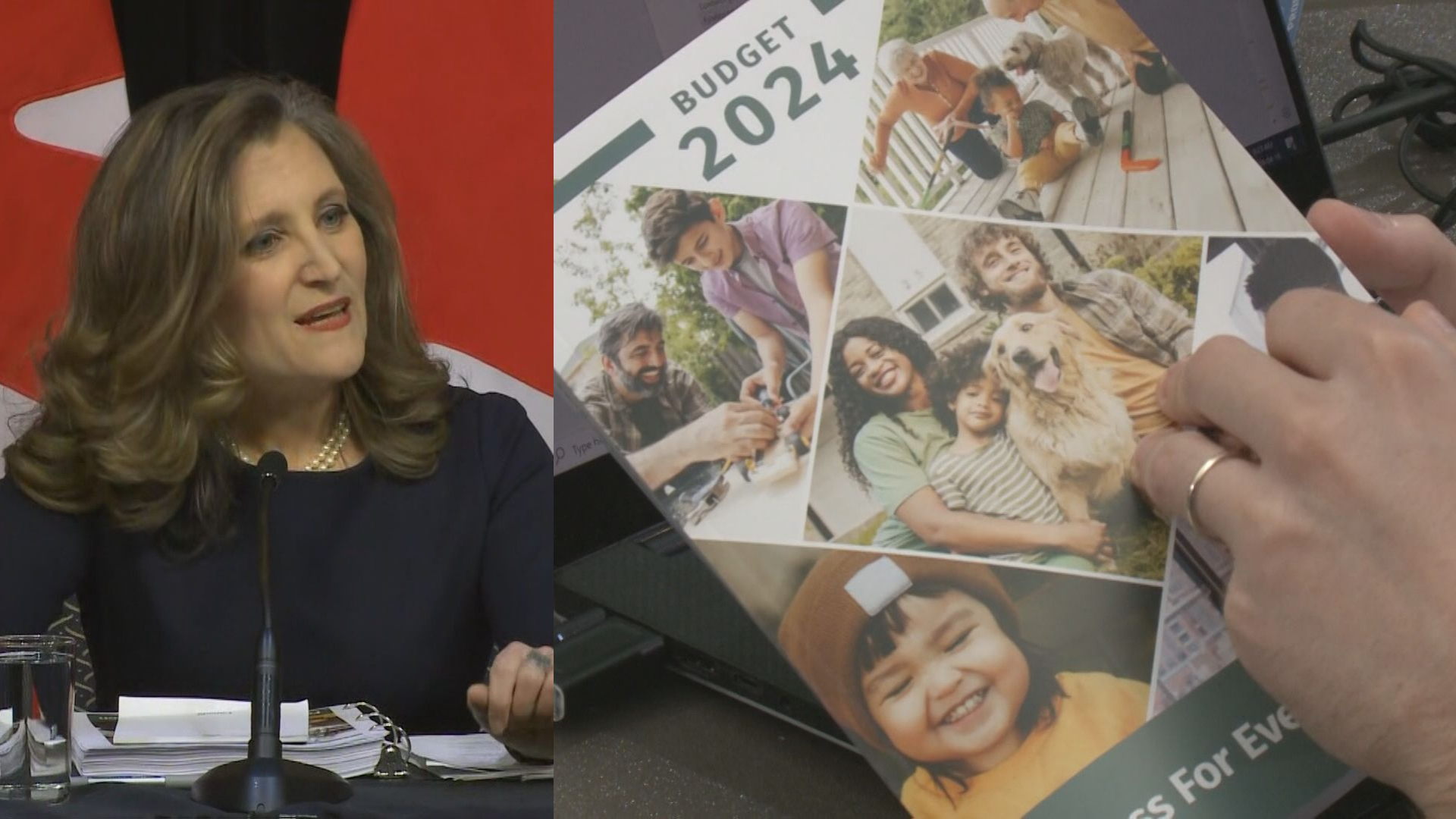

Amateur wildlife photographer Paul Turbitt, photographing a toad (and not a turtle, unfortunately) in a nesting habitat near Middle Sackville. By Kieran Delamont for HalifaxToday.ca

Amateur wildlife photographer Paul Turbitt, photographing a toad (and not a turtle, unfortunately) in a nesting habitat near Middle Sackville. By Kieran Delamont for HalifaxToday.caAnd there are no shortage of causes for Turbitt and other turtle-minded conservationists, whether that means advocating for better management of riverbanks, or for designing roads with turtle safety in mind. But lately, it’s been a proposed mobile home park development in Elmsdale that has brought the issue of turtles to the forefront once again.

The development is slated to take place in wood turtle nesting territory, he says. The city is aware of this, but has punted the issue to the province — “they have the legal responsibility for the wood turtles; the municipality does not,” municipal planner Shayne Vipond told councillors in April. The development, for the time being, is set to go ahead, wood turtles be damned.

For Turbitt, bureaucratic jostling is a distraction from the main issues: turtle habitat, for one thing; our human tendency to overlook the impact on ecological systems, on the other.

“They’re going to wipe out the turtles,” Turbitt says, of the 525-home development planned in the northwest HRM. “It won’t be the developer, it will be the 525 homes that he brings in — the garbage, and the explosion of racoons that will be hunting for something to eat.”

Our morning of turtle searching, however, ends with no turtle sightings — nothing but discarded eggs and the remnants of nests raided by predators.

For Turbitt, it’s not an uncommon thing to find. It takes a lot of eggs to maintain the turtle population — as many as 1,400 over a female turtle’s lifetime. If you’re in the habit of spending wet Wednesday mornings walking through a turtle’s nesting area, you get used to seeing it.

But turtles, Turbitt says, offer us some connection to our history. A turtle can live upwards of 60, 70 years, he says. You protect their nests now, he says, so that future generations still have turtles at all.

“If I help this turtle today, five generations down the road my great-great-great-grandchildren have the opportunity to see that,” Turbitt says. “But if I hadn’t, a turtle wouldn’t have lived. And that may be the last turtle. A turtle lays for 40 years — so which nest has the magic one?

“You tell me which nest it is, and I’ll forget about all the rest,” he says. “But until you can tell me which nest is the lottery winner today, then every nest deserves that protection.”

. By Kieran Delamont for HalifaxToday.ca

. By Kieran Delamont for HalifaxToday.ca