HalifaxYesterday : The Unknown Halifax Dockyard Transit Observatory

Posted Aug 2, 2022 04:44:00 PM.

In the early part of the 19th century, many ships continued to be lost along the route from Britain through The Virgin Rocks (off the southern coast of Newfoundland) to the St. Lawrence River. These losses resulted mostly from the inability to determine precise longitudes – extremely difficult because of the precise timekeeping required. Even a small miscalculation could put a ship miles off course. As well, the Admiralty charts in use at the time had been drawn up years before in the 1780s by Canadian cartographer Joseph Frederick Wallet DesBarres and lacked accuracy.

In 1822, Edward Sabben, Master of HMS Niemen (under Captain Edward Reynolds Sibly), had determined a longitude reading of 63° 33' 43″ from a survey of Halifax Harbour. In March 1828, the Admiralty ordered Rear Admiral Sir Charles Ogle, Bart., Commander in Chief of the North America and West Indies Station based in Halifax, to organize a comprehensive survey mission to map the coasts of the Gaspé Peninsula, Nova Scotia, the Bay of Fundy, the area of the Virgin Rocks, and would follow southward along the North American Coast to Bermuda. A small wooden structure built on a hill within the Dockyard served as a transit observatory and assisted greatly in further determining the Yard’s exact longitude.

Ogle chose Master John W. Jones and Admiralty Mate Horatio Jauncey of HMS Hussar to head the overall survey. Master Edward Rose of HMS Tyne, assisted by Lieutenant Henry Bishop of HMS Manly would conduct the survey of The Virgin Rocks. The massive two-year effort took from 10 August 1828 to 20 July 1830. The complete set of original log books from the Hussar’s voyages, kept by Midshipman Frederick Henry Stanfell, are housed at the Nova Scotia Archives (MG7, Vol. 13A, Books 1, 2 & 3).

The seven original HM Ships reported to have been involved in the survey were as follows: Ogle's flagship, Hussar (Captain Edward Boxer; Master John W. Jones), HMS Tyne (Captain White [later, Richard Grant; Master Edward Rose]), HMS Columbine (Captain Crole [later, Commander John Townshend; Master John Yule*), HMS Manly (Captain William Field [later, Lieutenant Henry W. Bishop; Master Isaac Mowle]), HMS Acorn (Captain Edward Gordon; Master William Clarke Purver*), HMS Contest (Captain Edward Plaggenborg; Master A. W. Baxter) and HMS Ringdove (Captain Charles English; Master Thomas Warwick).

All ships were supplied with the latest chronometer technology available. Unfortunately, both Acorn and Contest along with all officers and men were lost at sea during bad weather in April of 1828.

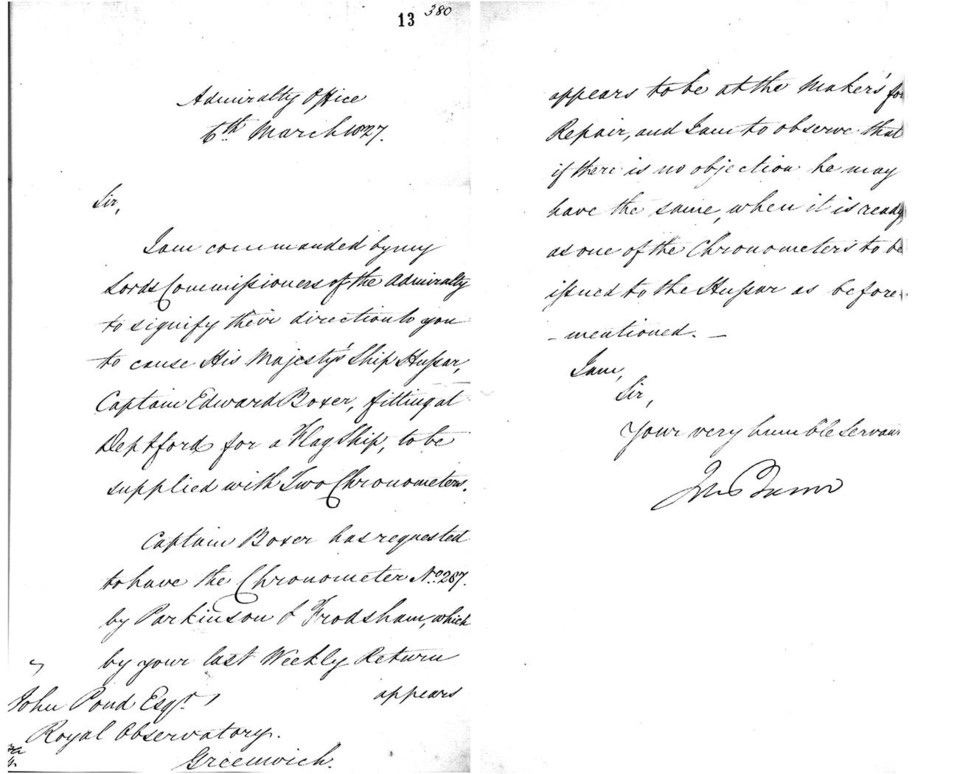

A June 2010 paper, “The Expansion of British Naval Hydrographic Administration, 1808-1829” by Adrian Webb, Archive Services Manager at the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office at Taunton UK, proved extremely helpful. The following are transcripts of Admiralty letters, copies of which Adrian kindly forwarded to me.

Captain William Edward Parry, Hydrographer to the Navy, to Ogle 1 March 1828:

“…The principal methods to be recommended for the determining of the absolute longitudes of places, are: occultations of fixed stars by the moon; solar eclipses; eclipses of Jupiter's satellites; and lunar distances; and these may be considered as capable of accuracy in the order in which they are here stated. Any observations of this nature, carefully conducted, will possess great value, especially if made at places frequently visited by ships, such for instance as Halifax, Quebec, and Bermudas. The whole of the data of such observations should be carefully preserved and transmitted to the Admiralty.”

“…For the North American Station, Halifax should be considered as a first meridian; some decided and well known spot being there fixed upon, where observations may be made without interruption, and to which all future observers may refer without the possibility of mistake or confusion. Whatever spot is thus decided upon it would be useful to perpetuate it by a large flat stone, and having cut upon it the word “Observation”…

In a letter to John Wilson Croker, Secretary to the Admiralty, dated 17 November 1828, Rear Admiral Ogle lamented that he could not depend on most of the chronometers at his disposal and requests that three more instruments be sent to him. These had been dispatched on 11 March via the ship HMS Champion. Ogle also mentioned that he borrowed the transit and telescope from King's College in Windsor “to ascertain correctly the longitude of this place [Halifax Dockyard], by means of occultations of the Stars etc. and the Moon's transit over the Meridian.”

Margin notes by Croker on the folder containing this letter and dated 23 December show he suggested to Captain Parry that he examine Ogle's revisions and make the decision whether to send the requested chronometers. Margin notes written by Parry on the same folder and dated 26 December state:

“The reports accompanying this letter are by far the most valuable and important ever transmitted to this office by ships not specifically employed by the Surveying Service. I think the Chronometers should be furnished as the Admiral requests, and I beg to suggest whether as an encouragement to such exertions, their Lordships would not be pleased to express by their their approbation to Sir Chas. Ogle and the Officers who have obtained the observations.”

In an excerpt from another transcribed letter from Adrian, dated 25 November 1828 and completed on 1 January 1929, Ogle wrote to his friend Parry:

“The little observatory on the Hill in the Dock Yard is completed, and I think will answer very well. We shall begin our observations immediately, for the purpose of ascertaining the longitude of the Dock Yard exactly, which has been considered the Meridian.”

Available literature regarding the observatory’s appearance remains vague at best. There is a reference in an article by D. A. Story contained in the records of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. Vol. 22, “H.M. Naval Yard, Halifax, in the Early Sixties”, p. 56, contains the following passage:

“Just beyond this, on the right stood Observatory Hill, long since cut down to enable a drill ground for the sailors to be laid out, but which was in the early days surmounted by a wooden block house, known as Fort Coote, and later by an octagonal Observatory from which it took its name.”

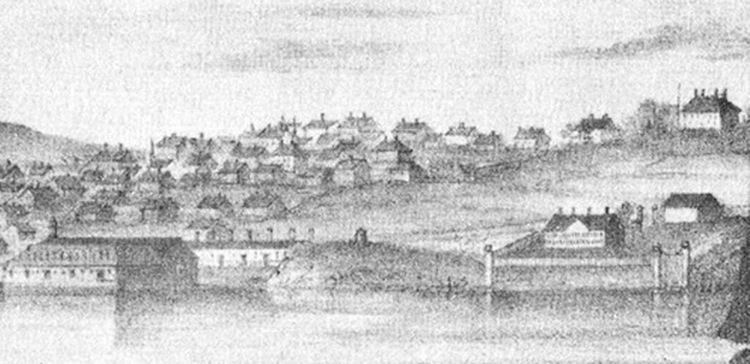

Fort Coote was torn down ca. 1800. A section of a drawing by William Eagar published in 1839 entitled Halifax, From the Red Mill, Dartmouth, depicts a small building in the old Forte Coote location that resembles Story's description of the observatory. Eagar lived and worked in Halifax. His works were reputed to be “views taken on the spot and on stone.”

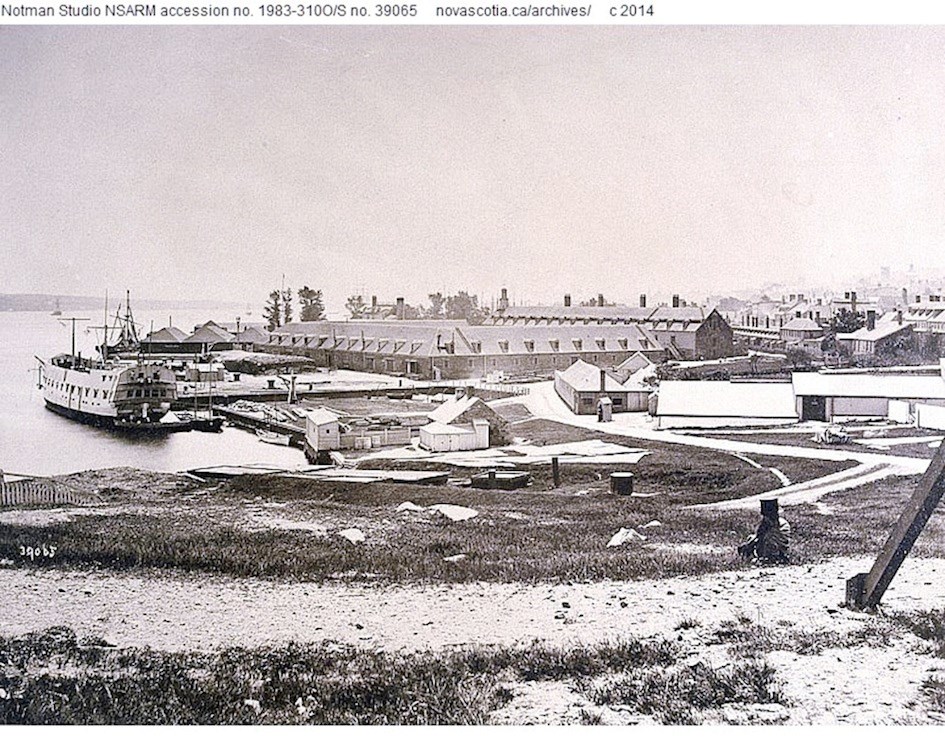

An 1859 hydrographic map from a survey by W. A. Hendry that had been corrected to 1869 by Edward J. Powell indeed shows the observatory in the former location of old Fort Coote at forty-seven and half feet elevation as depicted in William Eagar's drawing. An 1869 William Notman photograph from Observatory Hill looking southeast shows the view from near the observatory. The hill was levelled by the Royal Engineers between 1881 and 1883. The removal of the material was deposited on Intercolonial Railway lands by contractor Thomas Giles starting on July 28, 1884.

In papers published by Curator of the Provincial Museum in Transactions the Nova Scotian Institute of Natural Science, Rev. David Honeyman described the hill as the remnant of a glacial drumlin. He also noted that running through the coarse clay and sand were many different types of large boulders including “enormous” quartzite masses; “the weight of one was estimated by Mr. Nolan [the superintendent] at 13 tons.” The task of removal took nearly a year and three months to complete. Honeyman also wrote that “The hill disappeared finally, on November 4th, 1885, at 3:50 P.M., railway time; I watched its disappearance.”

In the March 2003 edition of The Griffin (Volume 28, No. 1), a publication of Heritage Trust of Nova Scotia, an article entitled “From residence to museum, Admiralty House boasts a varied and storied past,” shows a unique image on page 4. It is an 1845 drawing by Captain Michael Seymour of HMS Vindictive that features Admiralty House in the top centre. In the foreground, the drawing also depicts a clear representation of a small stand-alone four-sided structure atop a knoll on the right – with windows, a pointed roof, and a chimney. This can only be the transit observatory.

Captain Seymour's drawing appears to be an accurate representation of the observatory due to his faithful depiction of Admiralty House at the top centre. My onsite examination of the present day building at Maritime Command (MARCOM) and discussions with then Curator, Richard Sanderson, revealed that all of the house's main features as well as many intricate details presented in the sketch were indeed factual and precise. There is no reason to consider the appearance of the observatory in the foreground as any less accurate.

Upon completion of the survey, Rear Admiral Ogle lauded Master Jones and Mate Jauncey to the Admiralty for their extraordinary work (letter to Croker, dated 25 April 1830). Shortly thereafter, Jauncey was promoted to lieutenant:

“…Mr. Jones, the Master, and Mr. Jauncey, Admty Mate, of His Majesty’s Ship Hussar, have been most indefatigable; and shown such ability that I feel it my duty to recommend them to the notice of their Lordships.”

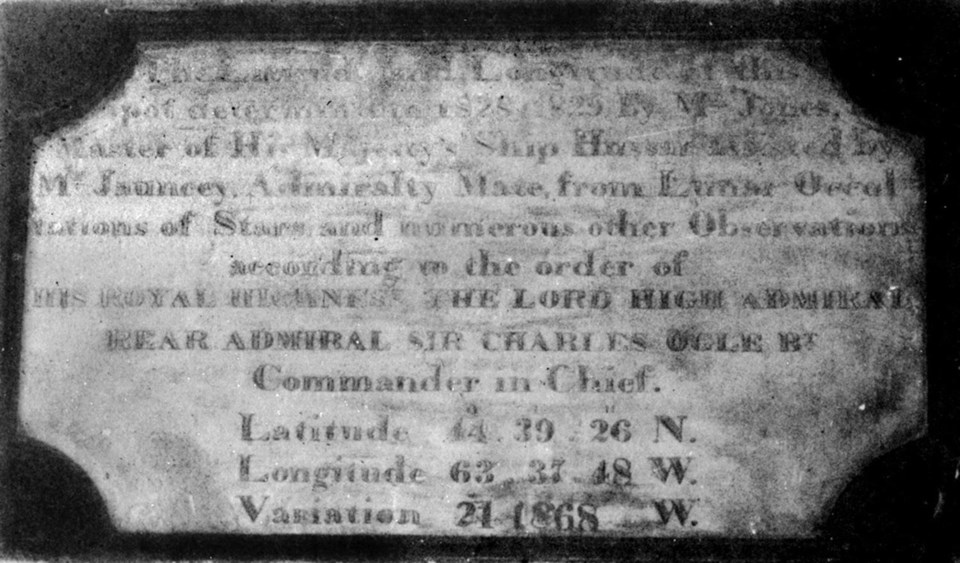

Ogle also erected a commemorative plaque in HM Dockyard that was subsequently placed on a wall of the Sail Store where it remained for decades.

“The Latitude and Longitude of this spot,

determined in 1828 and 1829 by Mr. Jones,

Master of His Majesty's Ship Hussar, assisted by

Mr. Jauncey, Admiralty Mate, from Lunar Occul-

tations of Stars and numerous other Observations

according to the order of

HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS, THE LORD HIGH ADMIRAL

REAR ADMIRAL SIR CHARLES OGLE BT

Commander-in-Chief.

Latitude, 44° 39' 26″ N.

Longitude, 63° 37' 48″ W.

Variation, 21° 18' 68″ W.”

The latitude 44° 39' 39″ and longitude 63° 35' 15″ (WGS84 reading) is the present estimated location of the HM Dockyard Observatory, just under the north side of the entrance to the Angus L. MacDonald bridge on the Halifax side.

Below is the only known photograph looking southeast from atop Observatory Hill in 1869, several years before it was levelled by the Royal Engineers (Notman photograph, Nova Scotia Archives).

For more detailed information and sources see the following: “Tracking the Elusive HM Dockyard Observatory” by Joel Zemel, halifaxexplosion.net/observatory.html; “Origins of the Halifax Dockyard Observatory + Appendices” by Randall Brooks and Joel Zemel, researchgate.net.