Maryland sues maker of Gore-Tex over pollution from toxic ‘forever chemicals’

Maryland is suing the company that produces the waterproof material Gore-Tex often used for raincoats and other outdoor gear, alleging its leaders kept using “forever chemicals” long after learning about serious health risks associated with them.

The complaint, which was filed last week in federal court, focuses on a cluster of 13 facilities in northeastern Maryland operated by Delaware-based W.L. Gore & Associates. It alleges the company polluted the air and water around its facilities with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, jeopardizing the health of surrounding communities while raking in profits.

The lawsuit adds to other claims filed in recent years, including a class action on behalf of Cecil County residents in 2023 demanding Gore foot the bill for water filtration systems, medical bills and other damages associated with decades of harmful pollution in the largely rural community.

Advertisement

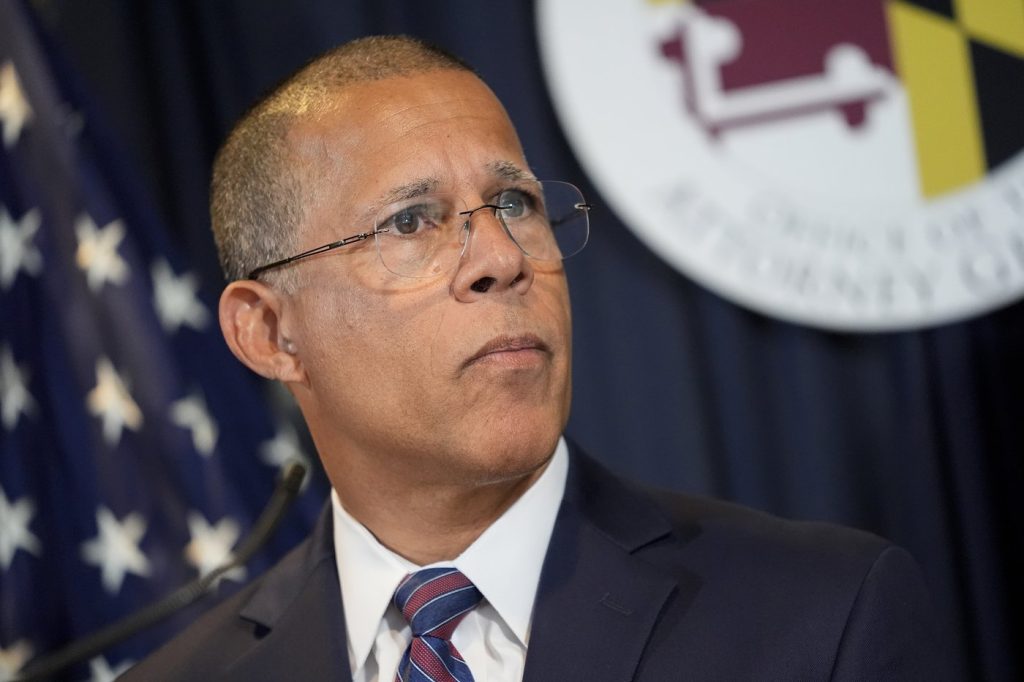

“PFAS are linked to cancer, weakened immune systems, and can even harm the ability to bear children,” Maryland Attorney General Anthony Brown said in a statement. “It is unacceptable for any company to knowingly contaminate our drinking water with these toxins, putting Marylanders at risk of severe health conditions.”

Gore spokesperson Donna Leinwand Leger said the company is “surprised by the Maryland Attorney General’s decision to initiate legal action, particularly in light of our proactive and intensive engagement with state regulators over the past two years.”

“We have been working with Maryland, employing the most current, reliable science and technology to assess the potential impact of our operations and guide our ongoing, collaborative efforts to protect the environment,” the company said in a statement, noting a Dec. 18 report that contains nearly two years of groundwater testing results.

But attorney Philip Federico, who represents plaintiffs in the class action and other lawsuits against Gore, called the company’s efforts “too little, much too late.” In the meantime, he said, residents are continuing to suffer — one of his clients was recently diagnosed with kidney cancer.

“It’s typical corporate environmental contamination,” he said. “They’re in no hurry to fix the problem.”

Advertisement

The synthetic chemicals are especially harmful because they’re nearly indestructible and can build up in various environments, including the human body. In addition to cancers and immune system problems, exposure to certain levels of PFAS has been linked to increased cholesterol levels, reproductive health issues and developmental delays in children, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Gore leaders failed to warn people living near its Maryland facilities about the potential impacts, hoping to protect their corporate image and avoid liability, according to the state’s lawsuit. The result has been “a toxic legacy for generations to come,” the lawsuit alleges.

Since the chemicals are already in the local environment, protecting residents now often means installing complex and expensive water filtration systems. People with private wells have found highly elevated levels of dangerous chemicals in their water, according to the class action lawsuit.

The Maryland facilities are located in a rural area just across the border from Delaware, where Gore has become a longtime fixture in the community. The company, which today employs more than 13,000 people, was founded in 1958 after Wilbert Gore left the chemical giant DuPont to start his own business.

Its profile rose with the development of Gore-Tex, a lightweight waterproof material created by stretching polytetrafluoroethylene, which is better known by the brand name Teflon that’s used to coat nonstick pans. The membrane within Gore-Tex fabric has billions of pores that are smaller than water droplets, making it especially effective for outdoor gear.

Advertisement

The state’s complaint traces Gore’s longstanding relationship with DuPont, arguing that information about the chemicals’ dangers was long known within both companies as they sought to keep things quiet and boost profits. It alleges that as early as 1961, DuPont scientists knew the chemical caused adverse liver reactions in rats and dogs.

DuPont has faced widespread litigation in recent years. Along with two spinoff companies, it announced a $1.18 billion deal last year to resolve complaints of polluting many U.S. drinking water systems with forever chemicals.

The Maryland lawsuit seeks to hold Gore responsible for costs associated with the state’s ongoing investigations and cleanup efforts, among other damages. State oversight has ramped up following litigation from residents alleging their drinking water was contaminated.

Until then, the company operated in Cecil County with little scrutiny.

Gore announced in 2014 that it had eliminated perfluorooctanoic acid from the raw materials used to create Gore-Tex. But it’s still causing long-term impacts because it persists for so long in the environment, attorneys say.

Advertisement

Over the past two years, Gore has hired an environmental consulting firm to conduct testing in the area and provided bottled water and water filtration systems to residents near certain Maryland facilities, according to a webpage describing its efforts.

Recent testing of drinking water at residences near certain Gore sites revealed perfluorooctanoic acid levels well above what the EPA considers safe, according to state officials.

Attorneys for the state acknowledged Gore’s ongoing efforts to investigate and address the problem but said the company needs to step up and be a better neighbor.

“While we appreciate Gore’s limited investigation to ascertain the extent of PFAS contamination around its facilities, much more needs to be done to protect the community and the health of residents,” Maryland Department of the Environment Secretary Serena McIlwain said in a statement. “We must remove these forever chemicals from our natural resources urgently, and we expect responsible parties to pay for this remediation.”

Advertisement

Lea Skene, The Associated Press