B.C. research suggests road salt linked to death and deformities in salmon

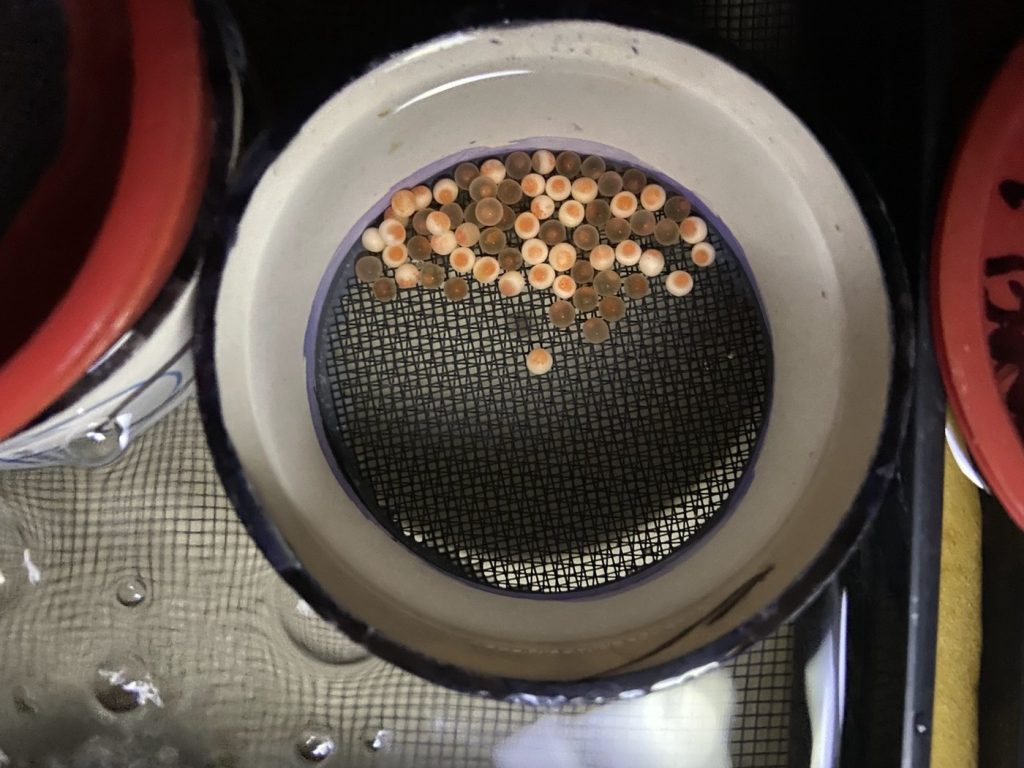

Researchers at the University of British Columbia have found evidence suggesting high levels of road salt in B.C. streams can cause death of salmon eggs and deformities in young salmon, and they hope their results will cause cities to adopt “smarter salting practices.”

UBC zoology students Carley Winter and Clare Kilgour are three years into a five-year study on the impacts of road salt on freshwater streams in the Lower Mainland and how they affect salmon eggs and young fry.

Their preliminary research, which they’re now preparing for peer review, suggests wintertime “pulses” of salt washing into streams used by spawning salmon can have negative effects on eggs and young fry at crucial times of their development.

Advertisement

Kilgour said the research was spawned by concerns from communities about potential harms road salting activities can have on salmon-bearing streams.

She said after moving to B.C. from the East Coast, she became “engulfed” in the “passion for salmon that there is on this side of the country.”

The research has so far found that salt levels in dozens of streams peak during the winter months and exceed water quality guidelines when salt levels spike in freshwater systems where salmon spawn.

Kilgour said lab tests showed a “shocking” magnitude of mortality in fish eggs when exposed to salt levels from eight to 10 times above freshwater guidelines.

Their research found that exposure to such salt pulses for 24 hours caused 70 per cent of coho eggs to die, but hatched fish weren’t nearly as negatively effected.

Advertisement

“We didn’t see those same kind of huge drops in survival,” she said. “They would be exposed to the same salt pulse that we had done on those eggs and they would survive that just fine.”

Winter said she was drawn to the Road Salt and Pacific Salmon Success Project because it’s “super collaborative,” involving researchers from UBC, Simon Fraser University, the British Columbia Institute of Technology and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Winter said the high mortality rate in eggs was a surprising finding.

“A 24-hour exposure, it’s not that long at all,” she said. “Short exposure concentrations we are frequently seeing in streams causing such significant mortality definitely was alarming.”

The results suggest that winter road salting is potentially dangerous to coho and chum salmon as they spawn in streams, and their embryos develop when road salting activities ramp up.

Advertisement

Winter and Kilgour said their research involved mimicking stream conditions in a laboratory setting, which was challenging given the number of confounding variables at play, but they’re confident in their findings after replicating their results multiple times.

“Definitely we hope that our research kind of promotes smarter salting practices,” Winter said. “I think there is sometimes a conception that we’re trying to ban the use of road salt, which is not the case at all.”

The pair suggest that individuals should be aware that one square metre of ground only needs about two tablespoons of salt for effective de-icing, and cities and other large users of salt could switch to brine to mitigate harms to environments where salmon spawn.

Several B.C. cities already use brine solutions instead of granular salt to deal with snow and ice, including both the city and district of North Vancouver.

City of North Vancouver spokeswoman Lyndsey Barton said it “has been using a brine solution for over a decade, given it uses far less salt and is more effectively distributed.”

Advertisement

The District of North Vancouver’s website says it stockpiles a “mountain of salt” each year, using upwards of 3,000 tonnes annually, employing a “fully automated brine machine” that can produce 10,000 litres of solution an hour.

The City of Port Moody uses both salt and brine depending on road conditions, and signed onto the road salt research project in 2023, with monitoring meters set up in local streams including South Schoolhouse Creek, Suter Brook Creek, and Noons Creek, its website says.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Jan. 2, 2025.

Darryl Greer, The Canadian Press

Advertisement