Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s famous name and controversial views collide in his bid for top health job

Posted Jan 27, 2025 08:04:21 AM.

Last Updated Jan 27, 2025 08:15:58 AM.

WASHINGTON (AP) — Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has said vaccines are not safe. His support for abortion access has made conservatives uncomfortable. And farmers across the Midwest are nervous over his talk of banning corn syrup and pesticides from America’s food supply.

The 71-year-old, whose famous name and family tragedies have put him in the national spotlight since he was a child, has spent years airing his populist — and sometimes extreme — views in podcasts, TV interviews and speeches building his own quixotic brand.

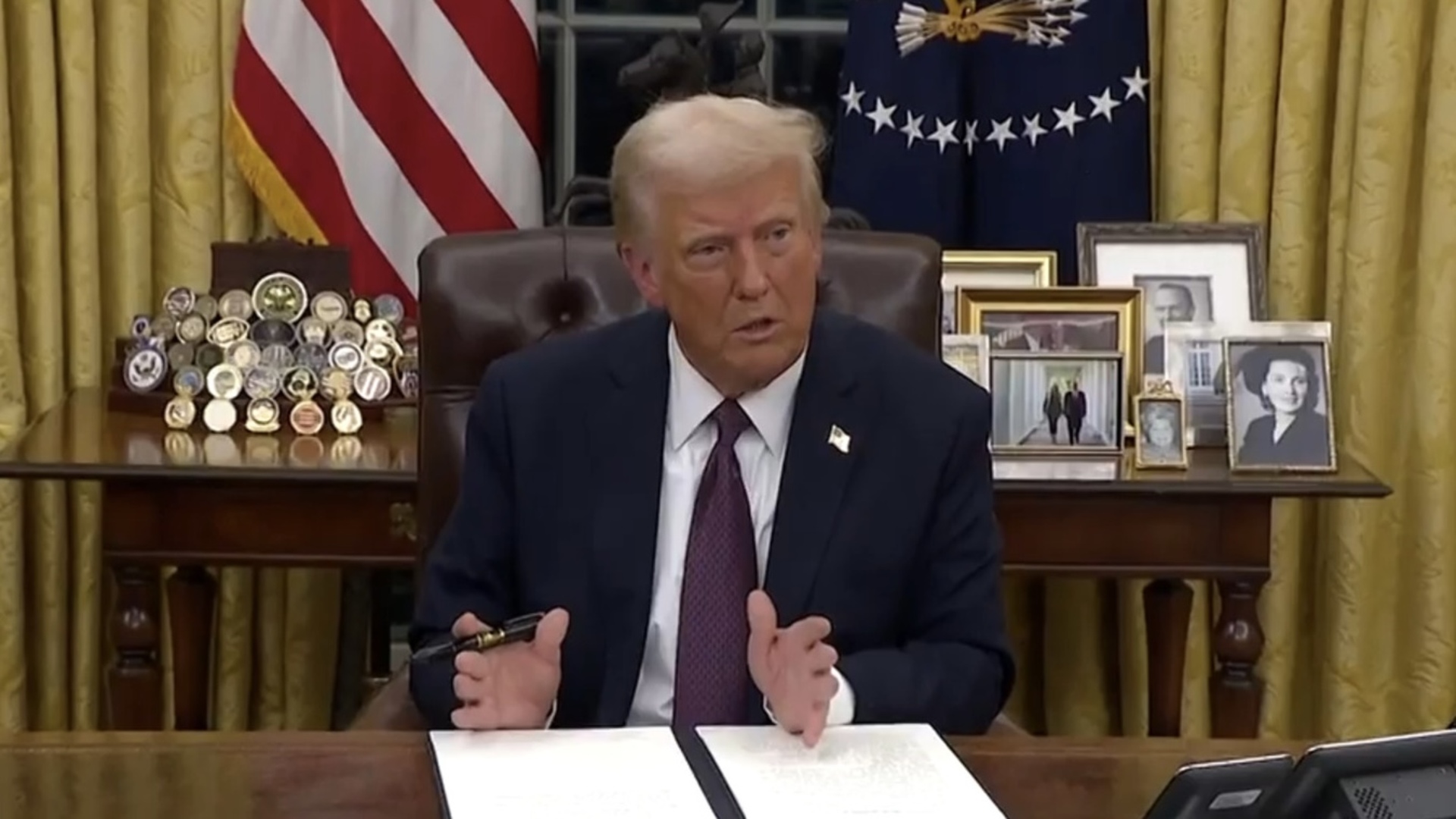

A son of a Democratic political dynasty, Kennedy is seeking to become the nation’s top health official under President Donald Trump. To get there, he’s softening those long-held beliefs, hoping to win approval from the Republican Party.

At stake is Kennedy’s control of the nation’s sprawling $1.7 trillion U.S. Health and Human Services agency, which oversees food and hospital inspections, health insurance for roughly half of the country and vaccine recommendations. The job would finally give him the kind of political power Kennedys have wielded for decades.

He made a long-shot bid for the presidency last year, following uncles John, who won the White House in 1960, and Edward, who lost his bid in 1980, along with his father, Robert, a leading contender who was assassinated after winning the California primary in 1968.

With a strong resemblance to his father and lawyer credentials to match, he found ardent followers who embrace the critiques he’s lodged against unhealthy foods, pharmaceutical companies and chemicals.

But he couldn’t get Democrats on his side, with some of his relatives shunning him over his vaccine views. His has been a flexible ideological journey, part liberal Democrat, part libertarian, and now, an adherent of the MAGA agenda after dropping out of the race last year to back Trump.

The president has since directed him to “go wild” on health. Together, they’ve even hatched a new slogan: “Make America Healthy Again.”

Kennedy’s aspirations now rest with the Republican-controlled Senate, where he can lose only three GOP votes if all Democrats oppose him.

As Kennedy’s confirmation hearings approach this week, he faces a coordinated effort to stop his nomination. A television and digital ad campaign is highlighting his anti-vaccine work. And former Vice President Mike Pence, a stalwart of the conservative anti-abortion movement, is lobbying against him, too.

Kennedy’s closest supporters believe he’ll prevail. He plans to focus on issues that have bipartisan consensus, like reducing food additives and increasing access to healthier foods. When concerns about his views on conservative priorities like abortion come up, he’s promised to follow Trump’s lead.

Then there is Kennedy’s biggest advantage — and maybe, too, his biggest liability for someone working under Trump — his star power.

“Bobby K. is coming in with a bigger microphone than any HHS Secretary,” said Calley Means, a close adviser to Kennedy.

Kennedy’s biggest hurdles: Anti-vaccine statements and tragedy in Samoa

Kennedy’s numerous remarks, anti-vaccine nonprofit and lawsuits against immunizations are likely to haunt him.

He’s rejected the anti-vaccine label, instead casting himself as a crusader for “medical freedom” who wants more research. He and Trump have vowed not to “take away” vaccines. To defuse criticism, he resigned from the Children’s Health Defense, his nonprofit that has filed dozens of lawsuits against vaccines, including the government authorizations of some of them.

But critics have argued that his work advocating against vaccine use has cost lives. Democrats are poised to home in on his social media campaigns and work in Samoa, the island nation in the Pacific Ocean where doctors say he and his anti-vaccine acolytes seized on a tragedy to campaign against childhood inoculations.

In 2018, two Samoan children died from botched vaccinations, prompting the government to suspend the childhood vaccination program.

Kennedy showed up with his wife, actor Cheryl Hines, to meet with the prime minister, health minister and other health officials in 2019. Kennedy says he promoted a “medical informatics system” that would “assess the efficacy and safety of every medical intervention or drug on overall health.”

Later that year, a measles epidemic killed dozens of infants and children.

Democrat Hawaii Gov. Josh Green, an emergency room doctor who organized flights loaded with 50,000 vaccine doses, doctors and nurses to administer inoculations, has led the campaign to highlight Kennedy’s role. He shared during one-on-one meetings with a handful of senators earlier this month what he witnessed there, including accounts from villagers who told them about Facebook posts that scared them away from vaccinations.

“He went there and used celebrity status to scare the country away from vaccinating,” Green said of Kennedy. “You have to ask yourself, ‘Why, RFK Jr., would you go to Samoa and do this to innocent people?’”

Kennedy has denied playing any role in the outbreak.

A Democratic group is running digital ads that accuse Kennedy of spreading misinformation in Samoa. The campaign is targeting senators in nine states, including Sens. Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Thom Tillis of North Carolina and John Curtis of Utah, which boasts a significant Samoan population.

Another they’re targeting is Republican Sen. Bill Cassidy, chair of the Health, Education, Labor and Pension Senate committee, which holds a hearing Thursday. Cassidy, who is also a doctor, stopped short of endorsing Kennedy after they met and is seen as swayable.

Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, who suffered from polio as a child, may also be in play. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, McConnell dipped into his own campaign funds to urge Kentucky residents to vaccinate against the virus.

Last month, McConnell sent a warning about attempts to discredit the polio vaccine.

“Efforts to undermine public confidence in proven cures are not just uninformed — they’re dangerous,” McConnell said. “Anyone seeking the Senate’s consent to serve in the incoming Administration would do well to steer clear of even the appearance of association with such efforts.”

A former vice president questions his commitment to ‘pro-life’ policies

Other conservatives have question Kennedy’s abortion views, after he said last year that it should be legal for full-term pregnancies. His campaign later clarified that he supports abortion rights until fetal viability, around 22 to 24 weeks.

In meetings with some senators, he’s promised to follow Trump’s directive on the issue.

Republican Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, for example, said he was convinced after talking to Kennedy that he would be a strong anti-abortion advocate.

But skepticism remains, with Pence’s advocacy group highlighting his abortion views in an ad campaign.

“RFK Jr. has made certain overtures to pro-life leaders that he would be mindful of their concerns at HHS, there is little reason for confidence at this time,” his group said in a letter sent to senators last week.

Senators ask: Will his ideas hurt farmers?

In Iowa, Kennedy’s nomination both excites and worries corn and soybean farmer Brian Fyre.

The sixth-generation farmer and Republican thinks Kennedy will offer a fresh perspective, but he also can’t afford the ban on corn syrup or pesticides that Kennedy has promised. If confirmed, Kennedy would oversee the Food and Drug Administration, which has the power to enact restrictions.

“We’d be pinched out. It would devastate rural, Midwest communities,” Fyre said. “You’re talking about a food supply for a nation. You can’t upend that without a viable alternative.”

Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa said he planned to offer some “educating” on agriculture to Kennedy.

Wisconsin Sen. Ron Johnson, a Republican from a dairy farm state, sees it differently, telling a crowd at the Heritage Foundation last month that Kennedy’s agriculture ideas are a promising part of a bigger goal: “to Make America Healthy Again.”

Amanda Seitz, The Associated Press