SS Whangape (1900): A Brief History of SS Mont-Blanc’s Sister Ship

Posted May 30, 2022 04:44:00 PM.

Although the connection between SS Whangape and the city of Halifax is indirect, knowledge of this particular vessel, the only sister ship to SS Mont-Blanc, is important from an archival perspective. “Whangape” (pronounced: fun gah' pay) is a Maori word meaning “waiting for the inside of the pipi” – a pipi being a bivalve mollusk native to New Zealand.

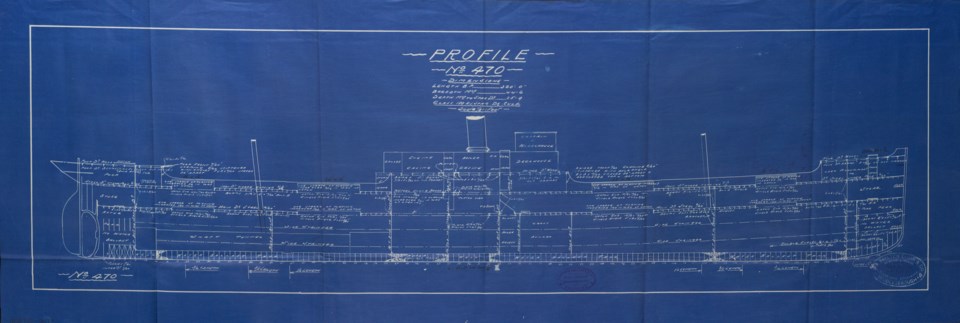

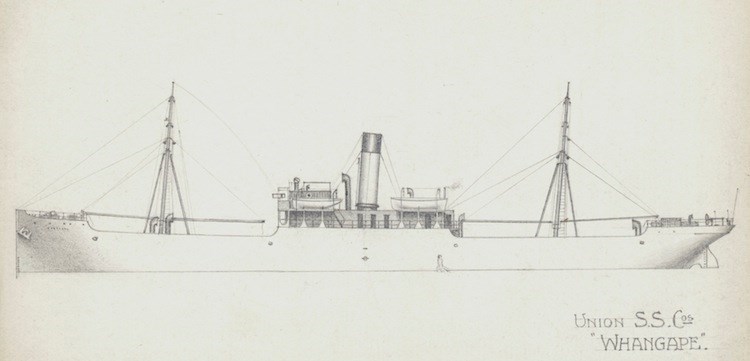

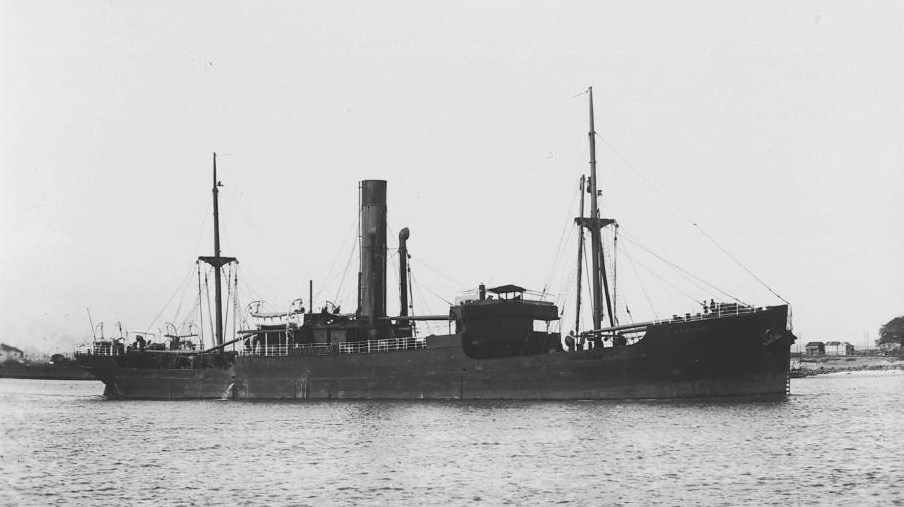

The designs of the two ships were identical during the initial planning stages. There are only three known images of Mont-Blanc, a French registered ship carrying an unprecedented cargo of volatile explosives into Halifax Harbour on the morning of 6 December 1917. Following a collision with the Belgian Relief ship, SS Imo, a 2.9 kiloton blast destroyed the North End of the city. Save for a deck gun, an anchor shaft, and countless scattered shards, little of Mont-Blanc remained. However, detailed plans for both ships and several decent-quality photographs of Whangape are extant. The information gleaned from this material is valuable to historians as well as to museum ship model makers wishing to reproduce accurate replicas of Mont-Blanc.

Whangape, official no. 110641 (ICS: RNKT), was a cargo ship constructed in 1899 by Sir Raylton Dixon & Co. in Yard 470 at Middlesboro-on-Tees. Thomas Richardson & Sons built her triple-expansion steam engine. She was originally laid down as Adriana for the British Maritime Trust Ltd., and launched as Asana on 16 December for Elder, Dempster & Co.. Originally sold to the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand Ltd., Dunedin, the vessel was involved in Indian trade for a short time but spent most of her life in Trans-Tasman trade.

Whangape was completed on 1 March 1900. On her maiden voyage under Captain M. J. Clarke, she carried a cargo of coal to South Africa. In July of 1900, Augustus James Hamilton Courbarron, the second youngest captain with the Union Steamship Company, sailed the new ship of the line. Below is an extract from a newspaper article covering an early onboard incident:

“On her maiden voyage which started at 31st March 1900 she took a cargo of coal to Durban. On the journey to Newcastle a heavy gale was encountered at Wilson's Promontory [4 July]. The Captain took shelter at Jervis Bay and on passing through the Heads the main steam pipe burst. If the accident had happened at sea the vessel may have been lost. On arrival at Newcastle she was taken over by Captain Courbarron.”

As of 1 January 1903, her USC deck officers included the captain, J. S. Adams; the chief officer, C. P. Reade; the second officer, W. Fretwell and the third officer, W. Allen. Proof of Whangape being the sister ship to SS Mont-Blanc (1899) is evidenced by both names appearing on amended profile and deck plans for yard 460, report no. 2620, and yard 470, report no. 2822. Mont-Blanc was the munition ship under French registry that collided with the Norwegian vessel SS Imo in Halifax Harbour resulting in the devastating 1917 Halifax Explosion. Construction of the sister ship was referred to in a letter from the surveyor to the Secretary in London. The ship's specifications – length (320.0'), breadth (44.8') and depth (15.5') – were identical to those of Mont-Blanc.

On 18 September 1908, Whangape broke her tail shaft on a voyage from Wellington to Suva and drifted helplessly for 18 days. Her master, Captain Chrisp, reported that the crew of 31 men had a very trying experience. The steamer SS Tofua was drawn to the Union ship's position off the Lautoka Passage on Friday, the 7th after having spotted a number of rockets fired from the stricken vessel. Although the crew had managed to temporarily repair the propellor, and despite the fact she had built up a good head of steam, the ship had been in danger of running aground on a reef. The men had passed a hawser around the propellor but the heavy swell prevented the broken parts from coming together as the ship rolled continuously. They decided to set the sails.

On the 22nd, two officers and four crewmen set off in a small boat to seek assistance. They reached Suva the next day and the ship. SS Atua was dispatched to find the missing vessel but was unable to do so. Meanwhile, back aboard Whangape, the propellor had been put into position once more but was found to be useless as the ship continued to drift. The lifeboats were provisioned and electric lights were affixed to the masthead so to attract the attention of passing vessels. Rockets and flares were set off and the sails lowered as the ship drifted westward. On the 24th they lowered 30 fathoms of chains to slow the drift and a second sea anchor was put out the following day but they drifted for 52 miles.

With her sails set once again, the next two days saw the vessel drift even further as her course took her into the Nevula Passage. They finally got the engines running again and cast off the anchors but the vessel still made very little headway. The slipping shaft only allowed Whangape to reach a speed of one and a half knots. She was thirty miles from Navula. Tofua was first observed on 30 September at 6:00 pm. It took another six hours before the hawsers connecting the two vessels had been fixed but the journey back to port was finally ready to begin. It was later reported that the officers and men of the steamer were all well and that in a worst case scenario, they had at least supplied themselves with 6 months of provisions along with 32 sheep.

The Royal Australian Navy chartered Whangape at the start of WWI in 1914. She was involved in operations against the German colonies in the Pacific with the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF). In the early morning hours of 25 August 1914, Whangape left Westport Harbour under sealed orders, commanded by Captain J. D. Frew. She met up with a convoy and later, the battlecruiser Australia at Rossel Island. They continued on to the island of New Mecklandburg, now New Britain. Whangape stayed behind with the submarines and another collier, Waihora, while Australia proceeded to rendezvous with Berrima and Encounter near Cape Gazelle. Whangape saw no further action and later that year, was returned to her owners.

Merchant mariners were concerned about the fighting in Timor in 1911 between the Dutch and Portuguese settlers. The British had a vested interest in the island because it was an important coaling station. The necessity for an appointment of a British Consul at Kupang, the capital of Indonesia, had been discussed in official and other circles for some time. Captain Horace White Parsons of Whangape had been transporting coal from Kupang to Sydney and reported to an Australian newspaper that such an appointment was a necessity. As reported in the Bunbury Herald, 29 August 1911, p. 3:”[Kupang is] the connecting link between Australia and the Far East, and an official should certainly be stationed there to guard the interests of the British trader.”

Captain White Parsons noted that while Whangape was in port, four British warships also arrived. He pointed out that the ships' complements had great difficulty in communicating with the residents, due to the absence of any English-speaking inhabitants. Parsons himself was considered for the appointment, but he suggested the only other Englishman on the island, a gentleman named Charles Mainwaring Pilliet, as a suitable candidate for the position. In February of 1916, Pilliet was appointed honorary British Consul at Kupang.

Like Mont-Blanc, Whangape was also involved in a collision at sea. Fortunately, there were no casualties in the 27 February 1924 incident with the McIlwraith McEacharn Ltd. owned freighter, SS Kooyong. The collision took place in Darling Harbour at Sydney, Australia. That early morning there was a moderate breeze. Kooyong was travelling light at 2 or 3 knots as Whangape, commanded by Captain Wilfred John Swales Eyre, rounded Miller's Point at 3 or 4 knots then picked up a tug. Both ships were near mid-channel on the eastern side after coming from the west. A lookout testified the former did not go straight to her berth and was struck by the USSC ship at a 35 or 40 degree angle.

Kooyong kept going in an easterly direction. Ten minutes later, the captain found he could not get enough way on to swing the ship to avoid some tugs and changed course toward the eastern shore. His ship was then about a length behind on her starboard side. 48 hours later, the vessel was examined and several plates were found to have been bent amidships, but had sustained no fractures. Examination at the dock revealed Whangape had sustained some damage to her bows as they were bent at right angles from port to starboard. The damage to both ships was severe to the amount of 2500 pounds each.

Whangape's captain insisted he was 350 feet off Balmain shore and well over in his own water, travelling at approximately 2 knots as he came in line with the coal wharf. He thought Kooyong was going to berth as she crossed the mid-channel, making considerable leeway. Witnesses reported that instead of backing in to one berth, the vessel headed southwest by south, coming round to starboard. To avoid a collision, the master of the tugboat swung to port with a taut line. The towline parted and Whangape sat nearly stationary in the stream. Seeing that a collision was imminent, the captain lowered the starboard anchor and went astern to minimize the force of impact. Kooyong came straight at him at 4 knots and came down on Whangape at right angles. Kooyong bounced off him, swung round and continued on. This evidence was corroborated by several witnesses.

Two weeks later, Admiralty Court decided the blame fell to Whangape's captain in assuming the other ship was going to berth. No blame was attached to the master, officers and men of Kooyong. However, the court stated that no costs would be allowed. In 1928, Whangape was sold to the Moller & Co. manager in Shanghai, Chun Young Zan, and renamed SS Nanking. She was broken up for scrap in 1935.

Sources: Lloyd's Register, 1933-34, SS Nanking; Lloyd's Register Foundation Heritage and Education Centre; Amended Plan of the Midship Section of a Steel Screw Steamer Mont Blanc, 6 May 1898; Tee Built Ships; NZ Ship and Marine Society; “The Steamer Whangape”, Auckland Star, Volume XXXI, Issue170, 19 July 1900; Photo of Captain Courbarron and his wife, Mary (1897), as well as the newspaper extract from The Hamilton Family History – A. J. H. Courbarron; Information regarding Whangape being lost at sea for 18 days from an article in The Argus (Melbourne, Australia), Saturday, 3 October 1908, p.19; Shipping News, Dominion, Volume 7, Issue 2238, 26 August 1914; Information regarding Charles Mainwaring Pilliet from a 2018 article by Michael Pringle; Naval Historical Society of Australia.