Her son needed help with addiction. Instead, he’s spending Christmas in an N.L. jail

Posted Dec 24, 2024 12:14:48 PM.

Last Updated Dec 24, 2024 03:16:10 PM.

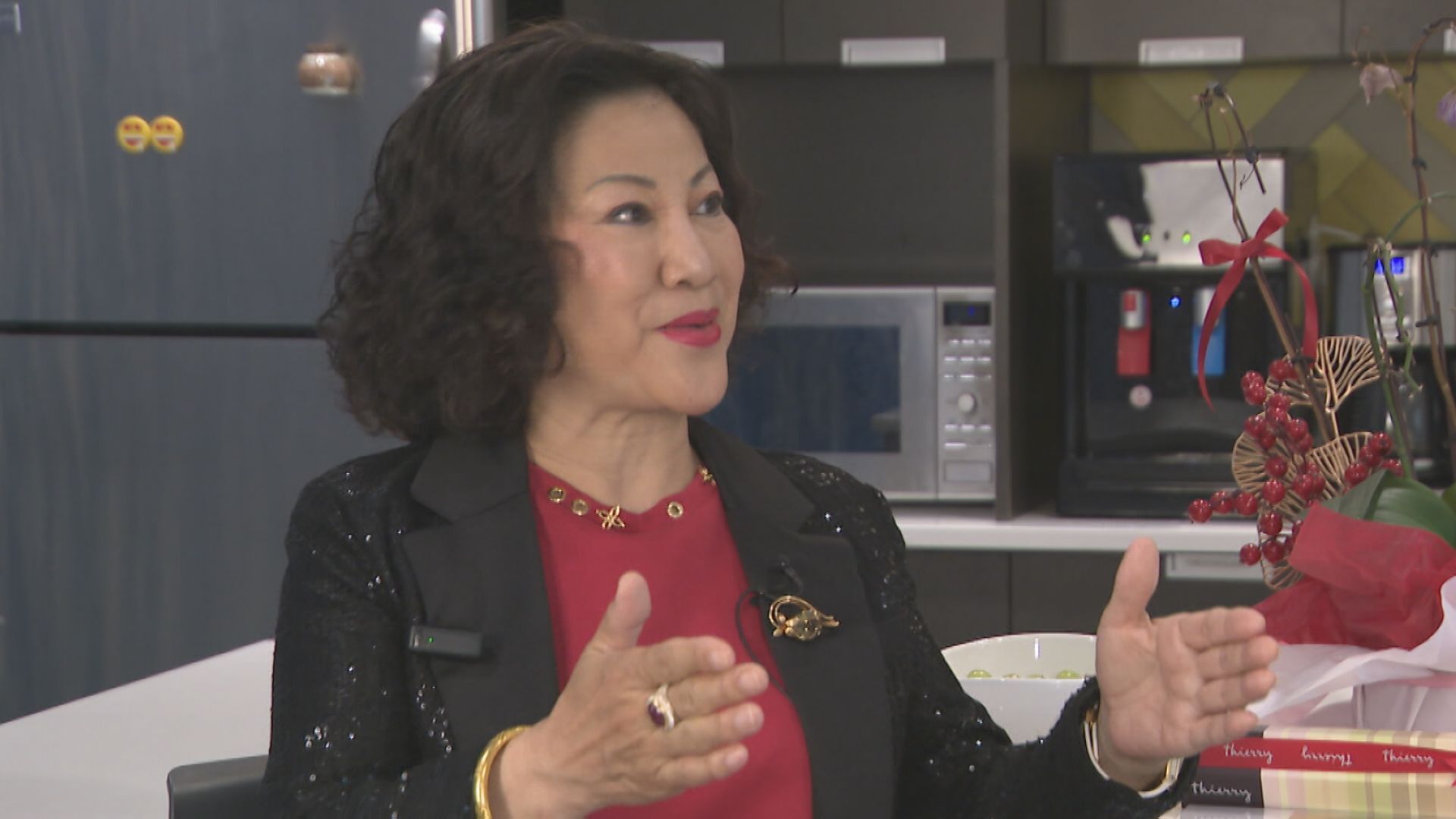

ST. JOHN’S, N.L. — As Gwen Perry prepares for a Christmas without contact from her son, who is locked inside a notorious Newfoundland jail, she wants people to understand that many inmates need help, not incarceration.

Her son, James Perry, is a loving father of two daughters who made good money working in the oilfields in Alberta before addiction and mental health issues upended his life, she said. Perry said she wants the public and the provincial government to better understand addiction — and what’s needed to support people who need help.

“I never dreamt that this was going to be happening to me,” she said in an interview Tuesday.

“Christmas is here and I know he’s hurting in there,” she added. “And I can’t even get another (video call) in until after Christmas, until after the holidays. I can’t even wish him a Merry Christmas now.”

James Perry is awaiting trial at Her Majesty’s Penitentiary, known as HMP, in St. John’s, N.L. The oldest part of the jail was constructed in 1859, and it is one of the oldest remaining provincial correctional facilities in Canada. The facility for adult men houses medium- and maximum-security inmates, people on long-term remand, and those awaiting transfer to a federal prison.

The jail is plagued by persistent staff shortages that lead to reduced programming and visitation, as well as extensive rodent and mould infestations.

“HMP is not a good place for anybody to be who has severe mental illness or addiction problems,” Perry said. “There’s no help.”

This is her son’s second stay at the facility; his first ended in July. She said he was released with nowhere to go and no supports in place, and he quickly spiralled back into drug use and theft. He now faces a host of charges, including breaching probation, stealing a vehicle and fraud under $5,000.

Perry said her son committed those crimes to get money for drugs.

“It nearly killed me to know what he was doing. He wasn’t raised that way,” she said. “I don’t even know if he remembers half of what he’s done, because the drugs had him messed up so bad.”

Perry fears her son will be released from the penitentiary in worse physical and mental shape. Now 37, he’s had health problems since he was 14, and he doesn’t get the care he needs inside the jail. Last Christmas, he called her over and over to say he was sick and not getting any medical attention, she said. When he was finally taken to the hospital, he had an infection so bad he was admitted for weeks.

His hospital stay was the first time she was able to hug him since he was arrested, she said.

“I’m sure I was holding on to him for an hour before I let go. Because he’s my son,” Perry said. “The two guards were there with him, and I said, ‘Excuse me, but I have to hold my child.'”

Two trailers have since been set up at the jail to offer more medical services for inmates, according to a statement earlier this year from the provincial Justice Department. And construction finished in October on a sprawling new 240,000-square foot mental health and addictions facility in St. John’s.

But more supports are still needed, particularly in rural parts of the province, where Perry lives. She said there are more and more dangerous drugs in the province’s small communities, leaving people in need of help.

“I’m looking for something that my son can come out and start a better life, and have a better life, and move forward with his life, and not come out like he did before, and go right back at the crime again,” she said.

“People need to research and learn more about addiction and mental illness. Because you know what? Tomorrow it might be them.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Dec. 24, 2024.

Sarah Smellie, The Canadian Press