HalifaxYesterday : The 1915 Artillery Shelling of Lucknow Street (5 photos)

Posted Jun 22, 2020 04:44:00 PM.

In the years leading up to the First World War, Halifax was recovering from an economic slump brought on by the exit of all British forces from the city in 1905-06. By 1915, with the ongoing widespread conflict in Europe, the mandatory port of Halifax had taken on the appearance of a booming garrison town once more. There was militia activity in and around six heavily fortified batteries, and the amount of ships carrying supplies and troops within the harbour and Bedford Basin was increasing at an exponential rate. The Royal Canadian Navy, established five years earlier, had a strong local presence with its harbour defence duties such as patrolling, minesweeping, maintaining an examination service, and controlling wireless stations. However, its ragtag fleet could offer only two obsolete cruisers, HMCS Niobe and HMCS Rainbow, to aid in the larger war effort.

The coastal defence battery guns protected Halifax against German raids by land or sea. They were operated by the Canadian government and manned by approximately 3,000 troops made up of some professional soldiers and a majority of our own Maritimes militiamen. No shots were ever fired from the batteries for the purpose of defense from an outside enemy up to the time of their decommission circa 1960. Although the big guns were situated in close proximity to populated areas, only a few minor accidents had occurred since the establishment of the batteries decades before – with two serious exceptions.

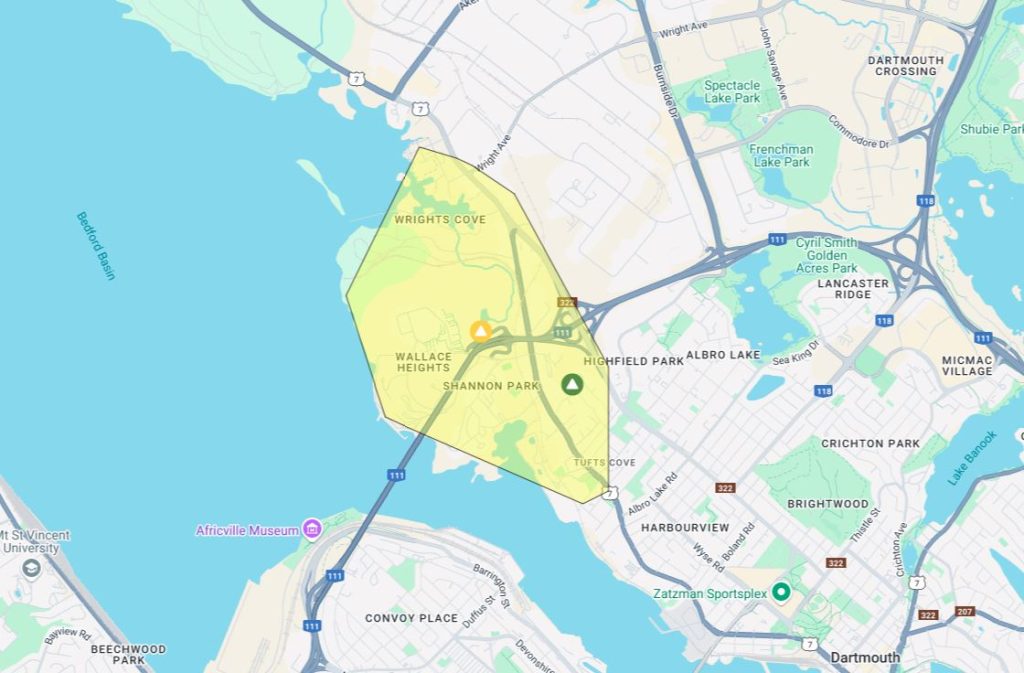

The first involved a one hundred-pound shell fired from a powerful six-inch gun at Fort McNab. It missed a target 1,500 yards out in the channel and landed in a farmer’s field on the Halifax side six miles away. No one was injured in that incident, but the huge shell landed very near a church. The other little remembered incident took place on the morning of 1 March 1915, and briefly caused unexpected panic and astonishment for many citizens, especially, for two families on Lucknow Street in the city’s South End. (See Images 1 and 2 above)

Due to wartime conditions, British Admiralty rules were in effect. The battery guns as well as two sets of “gates” – lines of anti-submarine nets in the harbour – guarded against incursions by German U-boats. One net lay across the channel at George’s Island and the other, from Fort Ives to Point Pleasant Park. On the day in question, a small Marine and Fisheries vessel, SS Brant, headed down to McNab’s Island to install a marker buoy near Fort McNab on the southern part of the island. All merchant ships

were processed at the examination anchorage off of Maugher (pronounced “Major”) Beach lighthouse below the fort before being allowed to proceed up the harbour. [A line of nets ran from this beach over to York Redoubt during World War II]. Brant was

working north of this location. (See Image 3 above)

On the return trip, as the vessel approached the Indian Point buoy near the northern tip of McNab’s Island, a 12-pounder gun from the Ives Point Battery suddenly lobbed an artillery shell that landed aft of Brant. The captain initially thought he was hearing the 12 o’clock gun from the Citadel. The Navy had given him the distinct impression he was not required to report to the examination vessel, so he ignored this signal from the fort. After all, he had not gone past the examination line which would have required clearance to get back inside the harbour. Only after a second round landed just 25 feet off of Brant’s bow, did the captain decide to stop his vessel. Quite unexpectedly, one of the shells had bounced off the water, flown high into the air, and headed towards the south end of Halifax. (See Images 4 and 5 above)

The powerful missile travelled a total of 3,700 yards. People reported hearing a whistling sound just before the shell landed atop a Victorian-style double house on Lucknow Street above an upper staircase in No. 10 owned by Mr. William O’Brien. The resultant explosion tore a dozen holes in the O’Brien’s roof and an 18-inch hole in the one adjoining. Steel splinters blasted through the partition into No. 12 owned by Clyde L. Davidson, smashing furniture and inflicting significant damage; one fragment penetrated six inches into an exterior wall.

Luckily, no one was inside the homes and there were no injuries. The two maids from the residences were outside hanging laundry together in the backyard and thought the heating system had suffered a serious malfunction. Upon her return, 25-year-old Miss Alice O’Brien was shocked to find a large group of people gathered on the street at her front door. Shattered windows lined the top level of the house – glass, plaster, and wooden shards were strewn all around. Engravings on a lump of steel later found amongst the interior debris showed the shell had been manufactured for the British government in 1897. Thus, the Department of Militia and Defense arranged and paid for all repairs to the double house.

This incident was a clear case of the left hand not knowing what the right hand was doing, and was duly deemed a communication failure between the militia and navy by their respective headquarters in Ottawa. The RCN had precedence in all matters regarding the regulation of ship movement within the harbour. However, not all military branches were familiar with the Halifax Defence Scheme, due in part to the confusion caused by the onset of war in August of the previous year. As yet there was no widespread use of radio communication, but the navy had neglected to implement its own protocol of having vessels in their employ display permanent identification flags to allow for clearance within the harbour. The men at Fort Ives had mistakenly assumed that the location of the examination service line lay beneath their battery across the water to Point Pleasant Park instead of at Fort McNab two miles further south. Soldiers were under orders to challenge any uncleared vessel.

Soon afterward, the militia adopted the location of the boundary line for the examination service below Fort McNab. They also determined that the battery’s large six-inch gun was much too forceful for firing warning shots at vessels, so it was replaced

with a non-lethal six-pounder that could produce a sizable spray at best when a shell hit the water. The smaller weapon’s lack of range and power ensured that damage to people and property in the city and surrounding area, as well as to ships and their

personnel, would be avoided. As an aside, the Halifax Herald covered the errant ricochet over the South End, but apparently, the matter was not considered serious enough to be brought up by City Council at subsequent meetings.

Although the double house on Lucknow Street is no longer extant, Alice O’Brien still resided at No. 10 in 1976 when she was 86 years of age. Historian Roger Sarty happened to be in Halifax researching the shelling incident and Miss O’Brien agreed to give him a tour of her home. At one point, she mentioned that during the Great War, a relative from England had written to her family about the bombing raids on British cities by German zeppelins. In their reply letter, the family stated that “we are being shelled

too, but by our own people!”

Source: Roger Sarty, “Incident on Lucknow Street, Defenders and Defended in Halifax, 1915,” © Canadian Military History, Volume 10, Number 2, Spring 2001, pp. 55- 59.